Here in Santa Cruz, as in many other places, there seems to be a great divide between the story that is told of this place, and what I’ve encountered in a year of life amongst it. This narrative, which I had encountered both as literal advertisements and as the words of friends and strangers, is one of exceptional natural presence and wonder. Santa Cruz, in its mountains, rivers, beaches, and coastal prairies, is a place of great stands of redwoods, historic salmon and steelhead rivers, marine vibrancy, and a community with great love for these things. It would be a mistake to say that these claims are outright false; indeed, there is great devotion found among the people who spend their time here. What I find so stark, however, is the role that Santa Cruz fulfills in constructing a notion of nature or wilderness for the 9 million people who live next door.

After six months living in the mountains, feeling vexed by a dichotomy of being surrounded by a forest which was and is almost entirely confined as private property, my partner and I moved to the coast in search of a neighborhood where the perpetual threat of cars (and Californian drivers) might not hold us back from an afternoon walk. We were fortunate enough to find somewhere which is a short ways from a seasonal drainage, Moran Lake, which feeds out in winter through a small beach across the street. We affectionately refer to it as “The Trees,” for the copse of Eucalyptus that encircle the lake and the path that adjoins it. In March of 2024, when we first moved to the area, The Trees were not all upright, but many had been torn aside, with root mats hanging open like a wound waiting for care. In time, tire tracks and saw marks have tended to most of the interruptions to the path, but trunks still rest on standing trees or stretch across the lake.

As summer closed the plug at the beach, and slowed the flow into this little pocket of water, we began to see flowers bloom, temperatures climb, migrating birds visit and rest, and, as with the rest of the county, an astounding deluge of tourists. Coming from Alaska, tourists are no foreign entity, if you’ll pardon the pun, but what was different was that so many came a short distance and stayed a short time. A camping trip, a day long visit to the beach, a hike in the redwoods, and the visitors had satisfied their hunger for time in the outdoors. In truth, I experienced a certain envy; in all my efforts, I have found it near impossible to reach the kind of nourishment I’ve come to rely on from visiting with my non-human neighbors. Instead, I find myself seeing too plainly to ignore, a drapery of settler land practices strewn across the region. The eucalyptus trees, like the ice plant thick on the sea cliffs, and the stilted thin redwoods packed into third growth forest, tell their histories to me every time I encounter them.

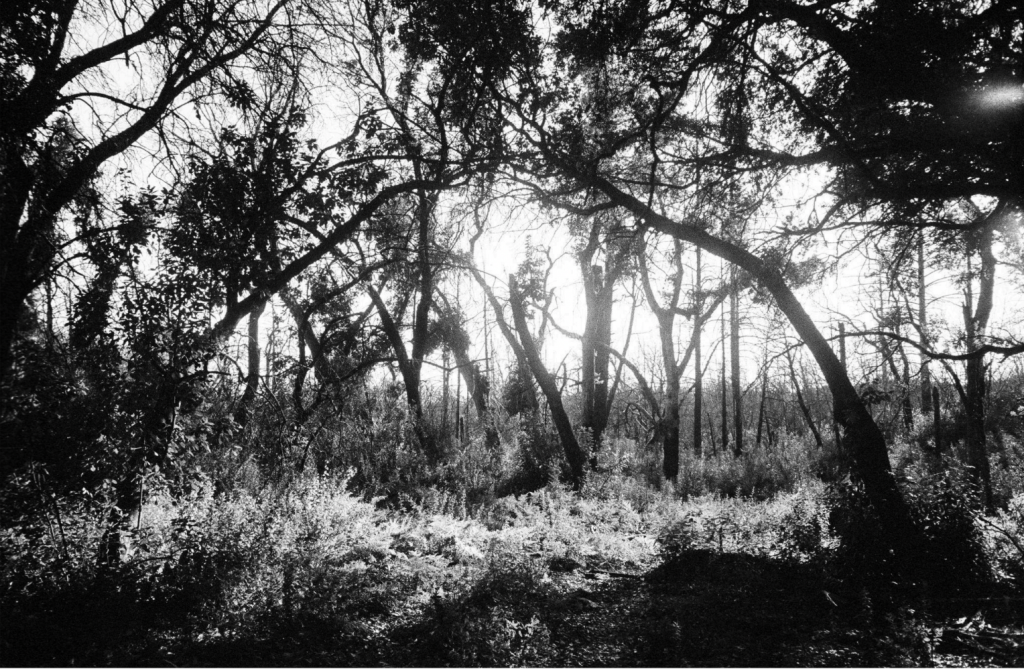

A fairy ring, as one might find in the woods that loom and trickle above and through campus, offers no defference in showing how it came to be. A mother stump may be pockmarked by the footprints of loggers, but their actions are clear regardless. The clones, which when first arising can be so thick as to appear like fur, often grow into a loving embrace; let this fallen tree forever be surrounded by its children. In another forest, and another time, this act of gratitude and recognition would strive upwards and fill the shining hole that punched through the canopy. Today, however, I find instead a sea of orphaned redwoods, each striving upwards as though pitted against one another by a manufactured scarcity. I can’t help but empathize. In the forest floor beneath, the consequences of this universal clearing manifests as a monoculture of absence. In stark contrast to the richness of old growth redwood forest, which is so dense with complexity that huckleberries and fern mats and salamanders drip from the crossing of trunks and aging trees might rest on their neighbor for a century or two before laying to rest, there is little life to be found in the duff. Instead, there is a dearth of understory growth, leaving the lower stretches of the woods to feel more like an empty lot than an intact ecosystem. Again, it’s important to me to be clear that these places are often visited, tended to, and thought of, by people who see this layered history and love the places as they are; people who build little fairy houses inside of fairy rings, and stack fallen logs to build forts where children play and touch the bark of the trees and hear of how the ancestors of those towering around them stood even taller. What scares me though, is to speak with people who, in learning that I’ve moved here from where I have, ask me “Don’t you just love it? Isn’t this place so magical?” And that all I can think of or find when I go to visit this magic is scars, and I feel a dizzying concern for what it might mean that millions of caring people see a place like this and understand it to be as it ought to be, for this is what they know as the tangible alternative to the built environment they otherwise inhabit. As summer closed the plug at the beach, and slowed the flow into this little pocket of water, we began to see flowers bloom, temperatures climb, migrating birds visit and rest, and, as with the rest of the county, an astounding deluge of tourists. Coming from Alaska, tourists are no foreign entity, if you’ll pardon the pun, but what was different was that so many came a short distance and stayed a short time. A camping trip, a day long visit to the beach, a hike in the redwoods, and the visitors had satisfied their hunger for time in the outdoors. In truth, I experienced a certain envy; in all my efforts, I have found it near impossible to reach the kind of nourishment I’ve come to rely on from visiting with my non-human neighbors. Instead, I find myself seeing too plainly to ignore, a drapery of settler land practices strewn across the region. The eucalyptus trees, like the ice plant thick on the sea cliffs, and the stilted thin redwoods packed into third growth forest, tell their histories to me every time I encounter them.

In this growing frustration and understanding of how I’ve seen people relate to and understand this place, it’s been all too easy to take a stance of directed blame and further diversion; how can each of these people be so blind to this manifestation of colonization and destructive land practices? The answer I’ve come to is embedded even more plainly in the question. Just as the settler state perennially reproposes and identifies itself as valid, certain, inevitable, and indeed indigenous, so too does settler colonialism train the settler to see the land as an extension of this, and to bury and invisibalize the histories which one might hear in the waves, bird song, or wind weaving between trees. It is no accident or mistake that a distortion of how this ecosystem once was and may yet again be is shown and shouted as normal, a site for leisure and uncritical acceptance as nature or wilderness. It is no coincidence that on no public land can one harvest acorns, that the only salmon one might bring home from the water are hatchery fish who have never known a natal stream, that even the Amah Mutsun must also be priced out of keeping a home here. It feels all too clear that to be close enough to know how broken things are, to care for what remains, is far too great a threat to the settler culture to ever be truly allowed, let alone to flourish. Still, the terns rest on the coast, hulking silver fish travel miles up the mountain streams, oak trees bend with the weight of their fruit, and gardens are kept so that the ways of being with this land can be found again. They hold on, as I do, for a future that hums in the soil and sand, waiting for a day to come when it is right to be whole again.